Left: George Mallory and Andrew Irvine © RGS/The Sandy Irvine Trust, from "Ghosts of Everest" ; Right: 1924 North Face locations © Pete Poston

| Photoanalysis | Routes & Maps | Video & Books | Contact Me ||

"I'm quite doubtful if I shall be fit enough. But again I wonder if the monsoon will give us a chance. I don't want to get caught, but our three-day scheme from the Chang La will give the monsoon a good chance. We shall be going up again the day after tomorrow. Six days to the top from this camp!"

--from George Mallory's last letter to his wife prior to disappearing on Mt. Everest with his partner Andrew "Sandy" Irvine in 1924

"My face is in perfect agony. Have prepared two oxygen apparatus for our start tomorrow morning".

- Sandy Irvine's last diary entry

Death came suddenly in the blink of an eye - Mallory and Irvine's Last Climb

© Pete Poston, April 20, 2013

Part 1 - The Ascent | Part 2 – The Descent

UPDATE: Winter, 2022: Originally this was my new theory of what happened to Mallory and Irvine on June 8th, 1924, but since then I consider it a "what if?" scenario. So much of what we know about Mallory and Irvine's climb leads to so many paradoxes, and there is none more so than Odell's epic sighting of the pair climbing the Second Step. But were they capable of this? The answer for me has always been "no", so this requires resorting to the First Step or the Third step and so on. Therefore I think it's worthwhile to investigate what could have happened if Odell was fooled by the shifting mists and didn't see anything at all.

I need to first explain how I have used the ideas of others, combined with my own thoughts.

First I need to acknowledge borrowing heavily from Audrey Salkeld and David Breashears’ excellent book “Last Climb: The Legendary Everest Expeditions of George Mallory”, where they have Mallory and Irvine avoiding the 2nd Step altogether, and following along Norton’s Couloir route instead, completely ignoring Noel Odell’s sighting of the pair ascending its precipitous slopes. I outline my own heretical reasons for doing so at the end of the narrative.

Gareth Thomas is another Mallory and Irvine researcher who has long theorized that they took the Couloir route as well, so I owe him a large debt of gratitude. And Tom Holzel and I agree on the route taken up the Yellow Band, and Mallory’s descent more or less vertically down it at the end.

Richard McQuet is an expert on Irvine’s modified oxygen set, and his explanations of how it functioned, especially the higher a climber ascended, was absolutely essential to the entire theory. Thank you Richard.

As you’ll see upon reading this, there are other ideas I’ve borrowed, including their separation and Irvine’s sighting by Xu Jing and Chhring Dorje Sherpa. All of this is in the literature and is nothing new.

Now for the new stuff.

I do have some new ideas of how oxygen was also used on the evening of June 7th, 1924, and offer a more in-depth explanation of how it was used for sleeping and the ascent, and how I am able to account for in what way all 10 bottles were used that were carried by them up to Camp 6.

I think I have a good idea on how the ice ax came to lie on the slab 250 yards east of the 1st Step, and I also tie in my discovery of rust marks on the face of Mallory’s altimeter with the events occurring there.

Perhaps the most original ideas I use here have to do with climbing rates (with McQuet’s insights). I do rely on climbing rates as calculated from their known oxygen supplies, and the location of the oxygen bottle at the base of the 1st Step. But here I differ from the others. I have elected to include a discontinuous use of oxygen, and a change in flow rates depending on the terrain, of the individual, and the effect of higher elevations, which is known to increase oxygen flow out open-circuit designs even though the selected flow rate is set to be lower. I also have them at intervals resting with the oxygen off.

These oxygen ideas are summarized in a Microsoft Excel file, and it can be downloaded from my website. I freely admit that I have juggled the climbing and flow rates to match known bottle capacities, but these match the terrain, and the resulting times are consistent with the known facts.

Finally, I am in debt to Eric Simonson and his recounting of his own attempt of the North Face with Ed Visteurs in 1987, where they climbed much of the same terrain as I have Mallory and Irvine doing when ascending the Great Couloir to the base of the summit pyramid. This theory would not have been possible without his input.

![]()

© Jake Norton, Mountain World Photography

“Well Sandy, are you ready?” Mallory asks his youthful companion, on the eve of Mount Everest’s most infamous summit attempt.

“Right George, everything’s ready to go, I’ve got the sleeping oxygen rigged up and the apparatus’ are ready for the morning”, Sandy replies, with more than a trace of tiredness in his voice. He coughs painfully, throat and sun-tortured face and lips burning from the effort.

“Good show. I can’t see us not making the summit tomorrow!” George breathlessly exclaims. “And well done, the oxygen has been working perfectly, and the summit is looking closer and closer”, he continues. Mallory stares at the summit so clearly etched in the high, thin air. Every rock and pebble on the summit slopes stand out in perfect relief as the orange-tinted alpenglow spreads across the North Face.

Mallory is full of nervous energy, forgetful as usual, and more than a little clumsy in the hypoxic thin air, drunkenly dropping the stove down the slope at Camp 5 when they were there the previous day, depriving Odell of the chance to make the brews so necessary to rehydrate at high altitudes when he occupied the tent after them.

Mallory doesn’t realize it, but he has been driving Irvine pretty hard, and Irvine of course, would never voice any complaints. His sun-burnst face, as recorded in his last diary entry, is causing him exquisite agony as he breathes through the oxygen mask on their ascent to high camp. Earlier, in desperation, he tried breathing only through the oxygen tube. Not a good idea, as he quickly realized due to his rapidly freezing face. He reluctantly uses the mask, but even more “sparingly” than Mallory wrote in his note to Odell earlier in the day.

Sandy is exhausted due to lack of experience at high altitude, and only his youth and British derring-do keep him going at Mallory’s manic pace.

George and Sandy, like Odell below them in Camp 5, enjoy a spectacular sunset as viewed from their tiny little camp perched on a precipitous slope at 26,700 feet, a tiny Whymper tent crammed full of all the detritus of climbing; sleeping bags, oxygen bottles and parts, cooking pots, and Brandt’s Beef Lozenges. When the sun sets, the cold immediately creeps in, and they quickly scamper into the tent and retreat into their warm, down sleeping bags.

It’s time for dinner. Fortunately Mallory hasn’t lost the cooker at Camp 6, but that’s mainly because Irvine has quietly tucked it away into a corner, out of harm’s way.

Soon the cooker is sputtering away in the thin atmosphere where the boiling point of water is only about 75 degrees Celcius. Irvine surreptitiously sticks his fingers in the boiling water to check the temperature, momentarily leaving them in to warm his hand while Mallory isn’t looking. Why not? No germ could survive 5 minutes up here, anyway. Come to think of it, it’s hard for a human being to live up here, too.

After an hour of lethargic preparation, the duo produces several cups of tea and an insipid, soggy mash of macaroni and beef tongue. Grab your nose and down the hatch with it, and try not to throw up on your companion.

Jesus, it’s so bloody hard to do anything up here. They make more tea and fill their thermoses for the morning. Remembering Norton’s bad experience with a loose thermos lid, they tighten them down a little more snugly. They luxuriate in the warmth, snuggling up like a baby in a womb.

Dinner finished and the dishes left for the goraks, Irvine connects spare oxygen bottles to his dismembered oxygen apparatus. Clever lad, when he redesigned the O2 apparatus, he had connected everything – regulators, valves, tubing – directly to the bottle. No need to drag the bulky apparatus into the tiny tent, simply disconnect the bottle and parts and carry them inside. As for the rest of the bottles? Well, they’re stored outside in the duralumin carrying racks, happily waiting for the morning assault. Two bottles each, having decided that they would “probably go on two”.

Mallory is pleased with his companion, and mentally congratulates himself for the millionth time to have chosen this enterprising young engineer.

Each climber has a full bottle for sleeping, as well as the partially empty bottles used on the day before. They decide to finish off the near-empty bottles while still awake, and set them on the lowest flow rate, about 1.5 L/min, enough for about 1-1.5 hours of resting (given the 90 atm consumed on the way up from the North Col).

The first bottle runs out at about 8pm, and they toss the empties out of the tent, listening to them clattering into the depths. Irvine connects two full bottles to the apparatus, and again at a flow rate of 1.5 L/min, enough for about six more hours of continuous use.

Warmly tucked away into their sleeping bags, they drift off into a dreamless sleep. The stones under the tent make it impossible to be completely comfortable, and the oxygen masks result in snores and spasms of breathing that would wake up the dead. But for the most part they sleep soundly under the soothing flow of oxygen.

The oxygen finally runs out, and they groggily wake up for their last day on earth. It’s about 4 a.m. – the expiration of the oxygen has made an excellent alarm clock. They pitch the empties outside and listen to them bonging down the slopes below, until they could hear them no longer in the vastness of the depths. Two full bottles remain behind in the tent. They might come in handy later, who knows?

A breath of wind sweeps up from the depths, carrying with it wisps of cloud and monsoon moisture.

![]()

Everything had been packed the day before in the afternoon hours after reaching Camp 6, which was around 1 p.m. in the afternoon. The thermoses haven’t spilled their contents, and so it’s time for a quick breakfast of tea and canned goods.

They’re ready by 5:30am - not bad. It’s light outside, not bright, but enough to see by. But so damn cold!

They tie their pre-prepared sacks of supplies and belongings to the outside of the oxygen apparatus, and turn on the oxygen supply. Mallory checks his watch and winds it up as he has always done. He taps the altimeter and sets it back to 27,800 feet, the altitude he had set the previous night based on the altitude Norton had given him.

He doesn’t realize that it’s a hundred feet too high.

The altitude has risen during the night. Mallory thinks about the decreasing pressure that would have caused that, but the day is bright, clear, and beautiful and everything’s looking good for the attempt. And the oxygen will give them a tremendous speed advantage, or so he thinks.

Oxygen set for 2.2 L/min, they set out on their great adventure.

What they don’t know is that the flow rate is actually higher because of the reduced atmospheric pressure and the open-circuit design of the apparatus (the same had happened the night before). The oxygen system was based on what was used by pilots during the Great War, except that it didn’t deliver a fixed mass of oxygen like the pilot’s system, but a fixed volume of gas in an open-circuit configuration, an important distinction.

This means that at the higher altitude, more oxygen would come out of the tank because there was less external pressure to hold it in, using more oxygen than they would have realized. Well, Irvine would probably have realized this, but with only fixed flow rates available, they didn’t have much leeway to adjust for this increased flow anyway. They would have been climbing at a rate closer to 2.6 L/min perhaps, further diminishing their oxygen supply.

Immediately above camp is a tricky little section of scrambling around a rotten limestone tower, a minor difficulty but an annoying way to start the day. But soon they are on the scree slopes and slabs that lie below the Yellow Band, which is looking much more steep and formidable than from down below.

The summit of Chomolungma seems closer and closer in the thin air, spurring them on and keeping their hopes high.

Mallory has already decided which way to go after a short reconnaissance the afternoon before (one of the porters had told Odell at the North Col that Mallory had moved the tent higher up, but he was mistaken, Mallory had only climbed a short distance up in order to scout the way ahead). Mallory had always wanted to climb vertically up towards the Northeast Shoulder, and catch the Ridge there, but there was no reason to do that now that Norton had filled him in on the easiness of the Yellow Band.

Based on this recce, Mallory makes for a prominent gully through the lower tiers of the Yellow Band, towards what is today known as the Climber’s Gully, the standard route taken by all climbers up to the Northeast Ridge.

Mallory feels a tang of doubt about the oxygen. Why are they not taking much less time than the oxygenless Norton and Somervell? Never mind, a quick calculation with the watch – 800 vertical feet an hour - and as good as Finch and Bruce in 1922 at the same altitude. Hey, that’s not too bad, but it should have been closer to 1000 ft/hr. The Climber’s Gully is full of hard snow, requiring step cutting, and the rocks are steepening around them. Time for the rope, which remains an umbilical cord between them for the rest of the day. Besides, who wants to carry the bloody thing? |

|

Many years later the tensile strength of the hemp rope was tested in a laboratory, and it was determined that the rope could only hold a short fall given the weight of the climbers. Mallory and Irvine might as well have left the rope behind for all the good it would have done them. But there’s more to a rope than safety. From “The Assault on Mount Everest” in 1922 – “A certain keenness of anticipation is associated merely with tying in the rope. We tied it on now partly for convenience, so that no one would be obeyed to carry it on his back, but no less for its moral effect: a roped party is more closely united; the separate wills of individuals are joined into a stronger common will.” |

|

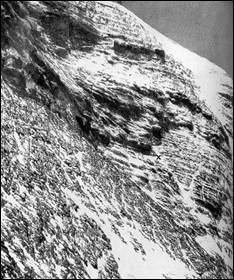

Another hour takes them halfway up the Band – 200 more feet of elevation at a much slower – and disappointing - climbing rate of only 200 feet/hr. Keep the flow rate high, and keep up the pace! It’s now 7:15am, and they are at the future location of the 1933 Camp 6 at 27,500’. Continuing along, they unknowingly follow the same route as Wyn Harris and Wager took during the 1933 expedition on their summit attempt. It’s a logical route dictated by the lay of the land. For safety, however, modern climbers climb directly up to the Northeast Ridge instead of Wyn Harris and Wager’s diagonal traverse in order to minimize avalanche danger.

![]()

Expedition cinematographer John Noel is ready to film Mallory and Irvine’s climb from his high eerie he had dubbed Eagle’s Nest, perched on a rocky shelf at about 22,000’, positioned more or less vertically above Camp3. Mallory had written to him the day before that it wouldn’t be too early to look for them at about 8am, another way to politely say “make sure you’re ready!”

Noel trains his camera on the summit pyramid, concentrating on either the summit ridge or the rockband below as Mallory had related in his note. Noel and Mallory had discussed where to film him several days previously, and was very specific where to find him (naturally Mallory would be unequivocal of where to see him during what could be the most famous climb in history):

“……Mallory told me himself, when he talked to me of his possible routes up the final pyramid and told me where to watch for him, that he expected to go up the northeast of the final pyramid, but if he found the Gully particularly bad he would take the eastern ridge, missing the Gully by passing across the head of it and gaining better protection from the west wind.” Noel’s compass bearings need to be explained. When Noel refers to the Eastern Ridge he means the NE Ridge. Now the direction associated with the “Gully” (the Great Couloir) is NE of the summit pyramid, when it is actually more like N-NE. |

Taken from Eagle’s Nest during N&S’s attempt. Based on the shadows, the footage was taken in the afternoon.© Copyright 2000-2005 The John Noel Photographic Collection. |

8am comes and goes and Noel sees nothing. A continuous watch is held by two porters through the 6X spotting scope coupled to the cine camera with a twenty-inch Taylor Hobson telephoto lens; at that magnification the climbers should have been easily visible. But nothing is seen, and at 10am the clouds move in and Noel can see no more.

It’s a pity that Noel didn’t have a view of the Yellow Band and the ridgeline below the 1st Step. Who knows what his camera might have recorded?

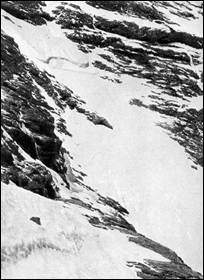

![]()

Once past the future location of the 1933 Camp 6, Mallory and Irvine traverse diagonally upwards, making for the base of the 1st Step. Their route through the upper Yellow Band leads them to the Northeast Ridge and the dangerous cornices overlooking the great Kangshung Face of Everest. Breathing more easily, they ascend for about 20 more minutes until they reach an obvious resting place a short way below the 1st Step. It’s time to change the oxygen bottles. Even though one of the climbers has a little bit more oxygen in their bottle, they save time and replace both at once. Why climb for only a short time and have to stop again? |

|

Their climbing rate from the 1933 Camp 6 location was about 250 ft/hr, taking about another hour and twenty minutes to reach the base of the First Step. It’s now about 8:30am.

Oxygen bottle number 9, according to the “Stella 5” list found on Mallory’s body 75 years later, only had about 100 atmospheres of pressure, while the rest of the bottles had 110 atmospheres. It’s unknown if the 110 atm still held the full capacity of 535 atm, since the lower temperature at high altitude could have easily caused the lower pressure.

The expedition had been given scales to measure the mass of oxygen in the bottles, which was between 8 and 8 ½ pounds, but were these used? If so, they would have had to have been measured by Irvine at Camp III when constructing the oxygen sets. But there is no record of it in Irvine’s diary where it would be expected to appear. So the pressures probably were measured at the oxygen dump below the North Col when they stopped for about 20 minutes on their way up to the North Col. They also could have conceivably been measured with the pressure gauges on one of the climber’s oxygen apparatus higher up the mountain. We’ll never know what the actual volume of oxygen was.

While resting below the great rocky mass of the 1st Step, the first mists are drifting across the lower North Face, and monsoon clouds are climbing up the Rongbuk Glacier far below. The barometric pressure is starting to drop – a Western Upper Disturbance is moving into the Everest region, but to the climbers, all looks well. A common occurrence on Everest – storms blow in from nowhere – much more rapidly than climbers in 1924 realized. |

|

Sandy takes a picture up to the summit with George in the foreground, bomber’s helmet and goggles making him look like some kind of insect. It’s the first picture taken that day

Irvine is thinking about the difficulties looming ahead, staring at the formidable Second Step. George follows his gaze, and knows exactly what he’s thinking.

“Sandy, lad, bugger trying to climb that cliff ahead.” Mallory says as he tucks his used oxygen bottle into a crack, “I have no doubt we could climb the 1st Step, but the 2nd Step looks far too difficult. Besides, the oxygen is going faster than I had hoped, and it would probably take our last tank just to climb it. No, let’s take the other way we talked about with Noel - the route into the Couloir. Traversing should take less oxygen, too.”

It doesn’t take much to convince Irvine. His stout heart would have tried it, but his inexperience would have prevented it. Mallory would have known this.

“You can see where Norton and Somervell climbed up from below, it looks reasonable, and easy to reach the spot where Norton traversed into the Great Couloir”, Irvine replies. Indeed, in 1933 Frank Smythe, without oxygen, took three hours from the 1933 Camp 6 to the Great Couloir following this route. It’s a sound climbing decision with oxygen.

All is going according to plan, the only surprise being the lower climbing rate that Mallory hadn’t expected. So they decide to cut their flow rate to 1.2 L/min. Once again, it’s actually higher, perhaps closer to 1.6 L/min instead.

Mallory and Irvine, having decided to traverse into the Couloir, can now make much better time, and take only about another 50 minutes to reach it. It’s now about 10am and the mists, which had been indecisive up until now, sweep up the great North Face, and from below John Noel can no longer see the Northeast Ridge and summit. Noel Odell observes the same thing on his solo upward trek between Camp 5 and Camp 6.

It’s time for another rest before crossing the Couloir. The mists are swirling around them now, but visibility is still good enough to proceed. They are within about 900 feet of the summit, and still have a little more than half a tank of oxygen left to them – about two hours more or less. It’s worth a shot at the top – even if the oxygen runs out, since they thought that descending without it would not be a problem. A rookie mistake that would have serious repercussions later.

“George”, Sandy rasps out, his voice barely audible after breathing the unforgiving, dry air. “I think we can make it across and climb up the other side. Let’s give it a try!” as he snaps a few photographs of the amazing views around them.

“We’ll do it, Sandy, we’ll do it! Norton arrived here much later, closer to noon. We’ve got the extra margin of time he didn’t have,” Mallory croaks back. After a 30 minute rest without oxygen (they’re much more fatigued at the higher altitude and take a longer break than before), it’s now about 10:30am - they really do have a good shot at making it, if the conditions remain good.

Mallory is juggling oxygen and weather in his mind; the monsoon is close to breaking, but why not take the chance since they were so close? Scanning the summit pyramid with a high-powered telescope from Base Camp, Mallory had seen no major obstacles on the way up to the summit. The route back from the Couloir wasn’t technically all that difficult, and even without a compass, keeping a bearing back should be relatively easy even in all the mist. If worse comes to worst, just keep moving east until they intersect the North Ridge, and then make their way down to Camp 6. Should be easy.

Should be.

With the route steeping ahead of them, they switch the flow rates back to 2.2 L/min (again, actually about 2.6 L/min), and set off. Mallory probes the snow in the Couloir with his ice ax. “Uh-oh”, he thinks to himself, “Tricky conditions ahead”. The slabs tilt down and outwards, are covered with loose stones and ice, and are dangerously smooth.

Barely visible in the snow are the shallow indentations of Norton’s steps from four days previously. Mallory feels a momentary sense of déjà vu – he feels like he has been here before.

|

|

|

Following Norton’s lead, he cuts a new step, and gingerly steps out into it, sinking his Tricouni nails into the ice with a reassuring crunch. Below them, the Couloir disappears into the swirling mists, little chunks of ice and snow dancing into the void, producing little rainbows of light. Mallory experiences a momentary spell of vertigo, but he’s used to this. Sucking on the oxygen, he makes the sensational crossing into the Great Couloir, marveling at the solo Norton’s grit and determination.

Irvine knows there’s not much of a belay possible, but he’s still feeling confident, and follows Mallory across the Couloir, careful not to trip on the rope as Mallory pulls it in.

Ahead lays an icy buttress, with even steeper slabs than before, and here the snow is looser because the area is shielded from the wind. In fact, Mallory had mentioned in his discussions with Noel about taking the Couloir route as a possibility if the West wind proved to be too strong, and they were now experiencing the consequences of loose snow deposited in the lee of the upper North Face.

“I think we’re almost as high as Norton got.” Mallory rasps to his partner. “It looks just like he described it, no way up the cliffs overhead, only some disagreeably steep slabs for a few hundred feet more, and then the Subsidiary Couloir exit. It’ll go!”

A gust of warmer air sweeps up from below. A few snow flurries start to fall. Mallory’s altimeter starts to increase in altitude because of the reduced atmospheric pressure, even though they’re resting for the moment, but remains unobserved in Mallory’s pocket.

Step by step, they traverse the steep, icy buttress. A gorak wings into view and quickly disappears into the growing mists. Strange, Mallory’s altitude-deadened mind thinks, it’s like pigeons on the roof in Mobberly.

Breathing becomes more laborious, thinking is dulled, and each step is accompanied by a deep-seated tiredness that only the will can overcome. That’s the way it is on the high mountains, physical stamina is one thing, but the pain and suffering is only conquered by sheer willpower.

Mallory and Irvine struggle on.

Suddenly the slabs of the buttress end, and the exit couloir is right in front of them. Still steep, with occasional outcrops of rotten rock, but the way is clear. An avalanche has cleared much of the loose snow out of the Subsidiary Couloir, leaving a firm base underneath that ax and hobnails soon overcome.

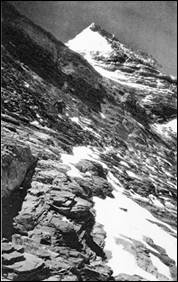

After two hours of climbing up the Couloir, Mallory and Irvine emerge below the summit pyramid. It’s about 11:45am.

Above them the summit teasingly pokes out of the now stronger mists and snow, slurries sting their faces, and despite the oxygen mask, noses become numb, and fingers and feet are starting to become uncomfortably cold. But the way is much easier.

In 1987, Eric Simonson and Ed Viesturs climbed up the same couloir (but approached from below), and stood on the same ground as Mallory and Irvine now did. Another decision presented itself – should they contour below the rock band that extended from the Third Step (the same one Mallory mentioned in his note to Noel), and climb up the summit snowfield, or traverse across the upper North Face looking for a break in the rockbands leading to the summit?

Simonson and Viesturs took one look at the traverse to the Third Step and said “no way!” In 1991 Simonson watched a Taiwanese climber, descending from the summit, get off route and try to cross the rockband. He soon gave up, and lay down in the snow and died. Marco Safredi snowboards across it a few years later, but Marco Safredi is Marco Safredi.

Decision made, it only took Simonson and Viesturs about 15 minutes to cross the snow slopes to the West Ridge, where they found the slopes above the Hornbein Couloir to be very steep, but passable. They would have made it, but a rock step on the West Ridge turned them back because they would have had to leave their rope behind in order to descend it. Wise climbers.

Mallory and Irvine looked across the rockband too, and came to the same conclusion. Best to continue traversing and hope there was a way up. The oxygen was now extremely low, but they were so close! They decide to push it as high as they can before the O2 runs out. Maybe, just maybe they can reach the top.

Two hours after reaching the Great Couloir, they reach their high point at 28,400 feet, almost directly below the summit 600 feet above them. But their oxygen has finally run out – they’ve gone as far as they can. They climbed across and up the Great Couloir at a pace of 200 ft/hr, and it took a total of two hours to do it.

Mallory is despondent; Irvine is too tired to care. They argue briefly about what to do, but a sudden freezing gust of wind makes their minds up for them. In that brief moment they felt the fingers of Eternity caressing them, and they knew that to continue was to die.

Mallory looks at his watch, and is dismayed to see that the crystal has fallen off and the hands are rubbing against the cloth of his jacket. One hand is missing.

How in the name of God did that happen? Somewhere on the way up, his left wrist must have banged against an outcrop of unyielding limestone, and he didn’t realize that the crystal of the watch had popped off (Mallory wore his watch on his left arm, face turned inwards).

Unnoticed, the crystal of the watch had slipped out of his sleeve and was crushed under his feet as he was chugging along, mind intent only on maintaining the rhythm of his climbing and breathing.

Mallory stuffs his watch into a pocket.

Irvine’s watch says about 12:10pm. They miserably turn back.

Part 1 - The Ascent | Part 2 – The Descent

![]()

Suggested Reading

- "Last Climb: The Legendary Everest Expeditions of George Mallory", David Breashears and Audrey Saulkeld

- "The Fight for Everest 1924", E.F. Norton

- "Ghosts of Everest: The Search for Mallory & Irvine", Jochen Hemmleb, Larry A. Johnson, Eric R. Simonson, William E. Nothdurft

- "The Lost Explorer: Finding Mallory On Mount Everest", Conrad Anker and David Roberts

- "The Story Of Everest", John B. L. Noel

- "Through Tibet to Everest", J.B.L. Noel

- "The Mystery of Mallory & Irvine", Tom Holzel and Audrey Salkeld

- "The Story of Everest", W.H. Murray

- "Everest: Eighty Years of Triumph and Tragedy", Peter Gillman, Leni Gillman, Audrey Salkeld

Articles and Editorials

![]() Harvey V. Lankford, MD, has written a paper documenting the origin of the term "Glacier Lassitude" as a diagnosis for the debilitating effect of altitude as experienced by members of the early British Everest expeditions..

Harvey V. Lankford, MD, has written a paper documenting the origin of the term "Glacier Lassitude" as a diagnosis for the debilitating effect of altitude as experienced by members of the early British Everest expeditions..

![]() My new theory about Mallory and Irvine's last climb, where I believe Odell's sighting was erroneous, and have them taking the Couloir route instead.

My new theory about Mallory and Irvine's last climb, where I believe Odell's sighting was erroneous, and have them taking the Couloir route instead.

Part 1: the ascent

Part 2: the descent

![]() Warwick Pryce is a new researcher who has arrived on the scene, and he has a new theory about how Andrew Irvine could have been the first person to stand on the top of the world.

Warwick Pryce is a new researcher who has arrived on the scene, and he has a new theory about how Andrew Irvine could have been the first person to stand on the top of the world.

Wim Kohsiek has a new interpretation of what Mallory's altimeter can tell us based on scientific applications of meterology.

Mallory and Irvine researcher Wim Kohsiek has two new thought-provoking articles about Mallory's watch and Irvine's location:

Mallory's Watch - Does it Really Point to 12:50 PM?

1924 Oxygen by Richard McQuet and Pete Poston

Why the Camera and Film are not Doomed to Destruction!

The Politics of Mallory and Irvine

Why Andrew Irvine Will Not be Found in a Sleeping Bag! Part 1 and Part 2 on ExplorersWeb

Chomolungma Nirvana: The Routes of Mount Everest

Rust Marks on Mallory's Altimeter

Mystery of Mallory and Irvine's Fate Google Earth Tour - my own ideas in 3-D with audio!

Little Known Free-Solo Ascent of the Second Step in 2001 by Theo Fritsche - I should never have written this - Anker and Houlding deserve credit for the first free ascent

Criticisms of the 2004 EverestNews.com search for Irvine --

The Mystery of Mallory and Irvine's Fate (with J. Hemmleb): Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5.

Mallory and Irvine - Comments on the 'real Second Step' route: Part 1 and Part 2

Conrad Anker's comments on the unlikeliness of a direct route up the prow of the 2nd Step

Articles about my heroes Walter Bonatti and Chris Bonington --

Spilling the Beans - Lino Lacedelli's Book "Price of Conquest: Confessions from the First Ascent of K2" Part 1 and Part 2

The Life and Climbs of Chris Bonington, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5 final - interview

About Me

Celebrating my 50th birthday on pitch 3 of Prodigal Son, Zion National Park, Utah

Celebrating my 50th birthday on pitch 3 of Prodigal Son, Zion National Park, Utah

In my free time, I love to photograph and hike the spectacular redrock wilderness of the Colorado Plateau - please visit my Colorado Plateau Homepage.

And for most of my life I've been fascinated with the history, people, and culture of the Himalayas and Karakoram - browse my Mount Everest Trek (1996), Overland Journey from Kathmandu to Lhasa (2000), and K2 Base Camp Trek (2007) webpages.

As for my employment, I work for Western Oregon University where I have been a Professor of Chemistry for the last 20 years. My research interests are in applications of Laser Raman Spectroscopy to such diverse fields as Nanotechnology, Analytical Chemistry, and even a bit of Achaeology through the study of rock art pigments found in the Colorado Plateau. You can access my academic webpage here.

Copyright (c) 2004-2022 Pete Poston. All rights reserved. Visitor's Agreement |